Accredited programmes

Materials

1. Introduction

Understanding the fundamentals and purpose of programme accreditation is crucial for educators involved in continuous professional development, especially in the context of inclusive digital teaching. Programme accreditation serves as a quality assurance mechanism that evaluates educational programmes against established standards. This process ensures that the programmes meet the necessary criteria for quality and relevance, thereby enhancing their credibility and recognition. Accreditation is particularly important in the field of inclusive digital teaching, where it guarantees that the programmes are designed to cater to diverse learning needs and promote equitable access to education.

2. Accreditation of Programs

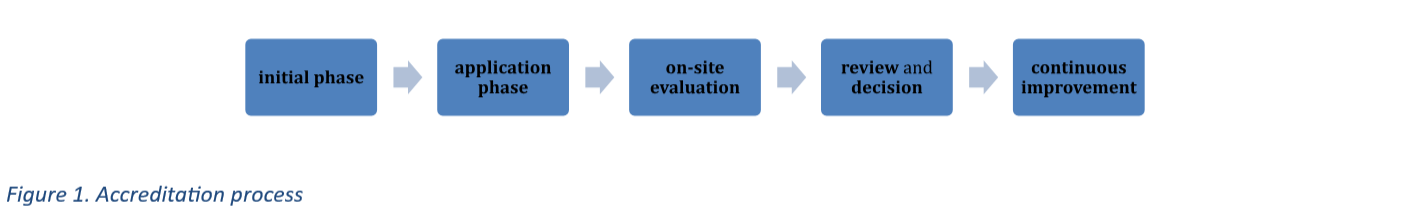

The accreditation process may vary between countries. Below are the basic and general steps that are important for the procedure itself. The accreditation process involves several phases, each with specific steps that must be meticulously followed. The initial phase involves preparation, where the institution assesses its readiness for accreditation and understands the requirements. This is followed by the application phase, where the institution submits the necessary documentation to the accrediting body. The documentation typically includes detailed reports on the programme’s objectives, curriculum, faculty qualifications, and student outcomes. For example, a programme focused on inclusive digital teaching might include documentation on how it integrates assistive technologies to support students with special needs (NECHE, 2018). The next phase is the on-site evaluation, where an external team of experts visits the institution to assess the programme’s compliance with accreditation standards. This phase often involves interviews with faculty, students, and administrators, as well as observations of teaching practices. The final phase is the review and decision, where the accrediting body evaluates the findings from the on-site visit and makes a decision regarding the programme’s accreditation status. Continuous improvement is a critical aspect of this phase, as accredited programmes are required to engage in ongoing self-assessment and enhancement to maintain their accredited status (Institute for Academic Development, 2024).

3. Documentation for the accreditation process

Preparing the required documentation for the accreditation process is a comprehensive task that requires careful planning and organization. The documentation must be thorough, accurate, and reflective of the programme’s quality and effectiveness. Key documents typically include the institution’s mission and objectives, detailed curriculum outlines, faculty qualifications, and evidence of student learning outcomes (The Joint Commission, 2024c). In the context of inclusive digital teaching, the documentation might also include how the programme addresses the needs of diverse learners through the use of digital tools and resources (The Joint Commission, 2024a). For instance, a programme might provide evidence of how it uses online platforms to create accessible learning materials for students with visual or hearing impairments (Institute for Academic Development, 2024). Effective documentation also involves presenting the information in a clear and concise manner, using visual aids and appendices to support the narrative (The Joint Commission, 2024b). This ensures that the accrediting body can easily understand and evaluate the programme’s compliance with the standards (The Joint Commission, 2024a).

4. Accreditation process in different counties

Accreditation of programs is carried out through various procedures, depending on the country and specific standards set by national accreditation agencies. Here are some examples of how accreditation is conducted in different countries:

United States of America

In the USA, accreditation is carried out by regional and national accreditation agencies, such as the Higher Learning Commission (HLC) and the Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE). The process includes a self-assessment by the institution, an external evaluation by experts, an on-site visit, and a final accreditation decision (New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), 2024a).

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, accreditation is conducted by agencies such as the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). The process includes a review of documentation, an on-site visit, interviews with students and staff, and the preparation of a report on which the accreditation decision is based (New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), 2024a).

Germany

In Germany, accreditation is carried out by agencies such as the Accreditation Council (Akkreditierungsrat). The process includes self-assessment, external evaluation, an on-site visit, and the preparation of a report that is reviewed and approved by the accreditation council (New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), 2024a).

Slovenia

In Slovenia, accreditation is conducted by the Slovenian Accreditation (SA). The process includes an application for accreditation, a review of the application, the appointment of evaluation experts, an on-site visit, the preparation of a report, and a final accreditation decision (New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), 2024a).

5. Recommendations and Good Practice for Accreditation Processes

In the following some recommendation and good practices within the accreditation process are presented.

- Self-Evaluation Report:

- Institutions conduct a thorough self-assessment to evaluate their compliance with accreditation standards. This report includes data on student outcomes, faculty qualifications, and institutional resources.

- Recommendations: Engage all stakeholders, including faculty, staff, and students, in the self-evaluation process to ensure a comprehensive and honest assessment.

- Peer Review:

- A team of external reviewers, often from similar institutions, visits the institution to assess its adherence to accreditation standards. They review documents, conduct interviews, and observe classes.

- Recommendations: Prepare thoroughly for the peer review visit by organizing documents and scheduling meetings with key personnel. Transparency and openness during the visit can lead to constructive feedback.

- Actionable Improvement Plans:

- Based on the findings from the self-evaluation and peer review, institutions develop plans to address areas needing improvement. These plans should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

- Recommendations: Regularly monitor and update the improvement plans to ensure progress is being made and adjust strategies as needed.

- Institutional Effectiveness:

- Institutions must demonstrate their effectiveness in achieving their mission and goals. This involves continuous assessment and improvement of academic programs and administrative services.

- Recommendations: Implement a robust system for collecting and analyzing data on student learning outcomes and institutional performance. Use this data to inform decision-making and strategic planning.

- Compliance with Standards:

- Institutions must comply with specific accreditation standards, which may include governance, financial stability, academic quality, and student support services.

- Recommendations: Maintain clear and organized documentation of policies, procedures, and outcomes that demonstrate compliance with accreditation standards. Regular internal audits can help ensure ongoing compliance.

Good Practices in Accreditation help ensure that the accreditation process is meaningful, constructive, and beneficial for institutions and their stakeholders (New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT), 2024b):

- Voluntary Participation: Accreditation should be a voluntary process driven by the institution’s commitment to quality improvement rather than external pressure.

- Local Control: The accreditation process should be led by local educators and practitioners who understand the institution’s context and needs.

- Transparency: Institutions should be transparent about their accreditation status, including the accrediting body, the date of accreditation, and any conditions or recommendations.

- Outcome-Based Evaluation:Focus on evaluating outcomes rather than prescribing specific methods. This allows institutions to innovate and tailor their approaches to meet accreditation standards.

- Continuous Improvement: Accreditation should be seen as an ongoing process of self-reflection and improvement rather than a one-time event.

6. Existing Accreditation Programmes

In practice, the principles of programme accreditation can be seen in various initiatives aimed at promoting inclusive digital teaching in higher education. For example, the European Schoolnet Academy offers accredited online courses for teachers that focus on innovative teaching and learning practices. These courses are designed to help educators integrate digital technologies into their teaching to support diverse learners (European Schoolnet, 2023).

Similarly, the Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa (TESSA) programme uses open educational resources to support teachers in African nations, adapting the resources to meet local needs and promote inclusive education. These examples highlight the importance of accreditation in ensuring that professional development programmes are of high quality and capable of addressing the diverse needs of learners.

Additionally, the Think College National Coordinating Center has developed a comprehensive guide for the accreditation of higher education programs for students with intellectual disabilities. This guide includes detailed standards and evidence requirements to ensure that programs are inclusive and meet high-quality benchmarks (Think College National Coordinating Center, 2024).

Another example is the Inclusive Higher Education Accreditation Council (IHEAC), which accredits postsecondary programs specifically designed for students with intellectual disabilities, ensuring these programs provide meaningful and inclusive educational experiences (Think College National Coordinating Center, 2024).

In the realm of inclusive digital teaching, practical examples abound. One notable example is the use of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles in accredited programmes. UDL is an educational framework that guides the development of flexible learning environments that can accommodate individual learning differences. An accredited programme that incorporates UDL principles would ensure that all students, regardless of their abilities or disabilities, have equal opportunities to learn. This might involve providing multiple means of representation, such as text, audio, and video, to cater to different learning preferences (CAST, 2024). Additionally, the programme might include training on how to use assistive technologies, such as screen readers and speech-to-text software, to support students with disabilities (UC Berkeley, 2024).

Another practical example is the implementation of blended learning models in accredited programmes. Blended learning combines traditional face-to-face instruction with online learning, providing a flexible and inclusive approach to education. An accredited programme that uses a blended learning model might offer online modules that students can complete at their own pace, along with in-person workshops and seminars (Rose, 2001). This approach can be particularly beneficial for students with disabilities, as it allows them to access learning materials in a format that suits their needs and provides opportunities for personalized support (CAST, 2024).

Furthermore, accredited programmes in inclusive digital teaching often emphasize the importance of creating an inclusive classroom environment. This involves not only using digital tools and resources to support diverse learners but also fostering a culture of inclusion and respect. For example, an accredited programme might include training on how to create inclusive lesson plans that consider the needs of all students, including those with disabilities, and how to use digital tools to facilitate collaborative learning. This might involve using online discussion forums, collaborative document editing tools, and virtual classrooms to create an interactive and inclusive learning environment.

7. Conclusion

Understanding the fundamentals and purpose of programme accreditation, the phases of the accreditation process, and the preparation of required documentation are essential for educators involved in continuous professional development for inclusive digital teaching. Accreditation not only ensures the quality and relevance of educational programmes but also promotes equity and inclusion in education. By adhering to accreditation standards, educators can develop and deliver programmes that effectively support diverse learners and foster an inclusive learning environment. The practical examples provided illustrate how accredited programmes can implement inclusive practices and use digital tools to enhance learning for all students.

8. References

CAST. (2024). The UDL Guidelines. https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

European Schoolnet. (2023). Reflecting Forward: European Schoolnet’s Annual Report 2023. http://www.eun.org/news/detail?articleId=11657266

Institute for Academic Development. (2024). CPD framework: learning and teaching. https://institute-academic-development.ed.ac.uk/learning-teaching/cpd/cpd

NECHE. (2018). Role and Value of Accreditation. Available Online, 5. https://www.neche.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Pp63-Role_and_Value_of-Accreditation.pdf

New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT). (2024a). Accrediting Body Home Countries. https://accreditation.org/explore-accreditation/country

New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT). (2024b). Best Accreditation Practices. https://accreditation.org/why-accreditation/best-and-worst-practices

Rose, D. (2001). Universal Design for Learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 16(3), 57–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264340101600308

The Joint Commission. (2024a). Accreditation Process Overview Fact Sheet. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/fact-sheets/facts-about-accreditation-process-overview/

The Joint Commission. (2024b). How Can We Help? https://www.jointcommission.org/what-we-offer/accreditation/accreditation-guide/

The Joint Commission. (2024c). Process Steps. https://www.jointcommission.org/what-we-offer/accreditation/health-care-settings/hospital/learn/process/

Think College National Coordinating Center. (2024). Accreditation for Higher Education Programs for Students with Intellectual Disability.

UC Berkeley. (2024). Universal Design for Learning. https://udl.berkeley.edu/

4. Continuous Professional Development Addition

Continuous Professional Development for Inclusive Digital Teaching – Part 2

CDPXX2

10 min

Participants will be able to:

- explain the key principles and importance of programme accreditation in education.

- describe the major phases and steps in the accreditation process

- develop, compile and organize the necessary documentation required for an accreditation process effectively

accredited programmes; documentation

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them (2022- 1 -SI01 -KA220-HED-000088368).