Policies for inclusive digital education

Materials

1. Assess your current situation

Policies in the context of Inclusive Digital Education refer to structured guidelines, principles, and regulations set by governments, educational institutions, or organizations to create fair and accessible digital learning environments. These policies outline specific measures to ensure that all learners—regardless of background, socioeconomic status, ability, language, or location—can participate in and benefit from digital education.

Policies for inclusive digital education might address several different areas of actuation such as (1) access and equity, ensuring all students have access to necessary digital tools, the internet, and any required assistive technology; (2) curriculum and content standards, establishing standards for creating digital content that reflects diverse perspectives, languages, and cultural backgrounds; (3) accessibility requirements, setting accessibility standards so that online platforms and resources accommodate various disabilities and learning needs; (4) teacher training and support, providing professional development for educators to help them use digital tools inclusively and understand diverse learner needs, and (5) monitoring and evaluation, implementing systems to regularly assess the effectiveness of these policies and ensure continuous improvement in inclusivity efforts.

1.1 Key Principles

When designing inclusive digital education policies, several guiding principles should be prioritized as Key Principles:

- Equity of Access: All learners should have reliable access to digital tools, internet connectivity, and necessary assistive technologies, regardless of their location, socio-economic status, or physical abilities. Policies must focus on bridging the digital divide to prevent exclusion based on economic or geographic factors.

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL): Policies should endorse UDL principles to create learning environments adaptable to diverse learning styles and needs. UDL emphasizes flexibility in the ways information is presented, engagement with the material, and assessment, ensuring that learning materials are accessible to all.

- Cultural and Linguistic Relevance: Digital learning content should reflect diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Policies must support the development of educational materials in multiple languages and culturally relevant content that resonates with learners from various communities.

- Data Privacy and Security: Protecting learners’ data is crucial in digital education. Inclusive policies must ensure that student data is handled ethically and with explicit privacy protections, particularly for vulnerable populations such as minors and individuals with disabilities.

- Professional Development: Teachers and staff require training in inclusive teaching strategies and digital tools to effectively support all learners. Policies should provide professional development opportunities to equip educators with the skills necessary to implement inclusive digital practices.

What impacts teaching is embedded in national and international policies and shaped by decision-makers and stakeholders. Institutions need to be part of these policy dialogues and public consultations, to strengthen the whole process of interacting, reflecting, and challenging these broader structures.

2. Categorizing policy levers

To systematically organize and arrange the study of the diverse policy levers influencing access and social inclusion in higher education, we differentiate among several types of policy instruments. Based on the typologies of Van Vught and De Boer (2015), four categories of instruments are distinguished: regulation, funding, organization, and information. These instruments differ in their capacity to affect behavior. Regulation and funding are generally understood to be “hard” or “strong” policy levers, while organization and information are seen as “weak(er)” or “soft” policy instruments.

- Regulation: Regulations are designed to mandate and prohibit, to endorse and to authorize. Regulations differ in the extent of restrictions imposed on the conduct of higher education institutions or students. Authorities govern access to higher education, establish entry criteria, and permit or prohibit certain schools from offering certain sorts of programs. Regulations may influence the processes or the substance of courses in higher education (see to Veerman (2010) for a difference between substantive and procedural autonomy). In unitary states, rules are formulated at the national level, but in federal states, they can be established at either the federal or state levels. In this research, the term regulation denotes formal (official) guidelines for access and social inclusion.

- Funding: Funding allows governments to employ financial incentives and penalties to shape behavior. Authorities may, for example, offer a premium to higher education institutions that successfully attract students from specific disadvantaged backgrounds. Additional funding incentives for universities comprise supplementary allocations for innovative teaching programs or pedagogical methods that cater to the requirements of students from underrepresented groups. Governments may directly target students by offering scholarships and grants to those in financial need.

- Organization: This area encompasses all operational actions directly impacting higher education frameworks. An illustration would be the implementation of a novel short-cycle program aimed at engaging minority student demographics or the recruitment of new educational career advisors inside secondary or tertiary educational institutions. Furthermore, national or local governmental bodies that assist students in selecting a certain field of study would be included in this category. Organizational factors pertain to the frameworks and protocols related to teaching and learning. One may include avenues to and within higher education (e.g., transition regulations between institutions and programs), options for part-time offerings, and the incorporation of online educational provisions (e.g., MOOCs).

- Information: Due to its unique societal role, the government frequently serves as a repository of information. Compared to other organizations, governmental agencies are often more adept at data collection and in formulating comprehensive, overarching assessments of social situations. Examples include providing access to data on student opportunities or disseminating projections of skills along with information regarding the availability and quality of education. Governments may utilize information and marketing initiatives to encourage certain student demographics to apply for and enroll in higher education.

Andrea (2019) provides details of this characterization, case studies, and policy examples.

3. Analytical framework for a digital education policy ecosystem

Facilitating educational systems to attain excellence and fairness in the digital era necessitates a comprehensive policy strategy. The scientific literature presents an analytical framework to examine the extensive and intricate effects of digitalization on students, educators, educational institutions, and the whole education environment.

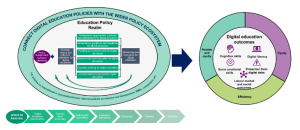

The analytical framework presented in OCDE (2023) is considered a reference here. It is intended to be comprehensive and encompass the complete spectrum of policies essential for effective digital education. The framework examines several policy levers in education, organized into eight analytical dimensions, along with their interplay within the larger policy ecosystem (Figure 3.1).

- Conduct a study of the ramifications of digital education policy across all tiers and for a diverse array of stakeholders both within and beyond the school system. The analytical framework consists of many layers of analysis, extending from the student level to stakeholders within the wider digital education ecosystem, such as EdTech businesses.

- Emphasize the extensive array of outcomes that digital education policy may affect. The analytical approach examines the impact of digital policy levers on various outcomes (including cognitive and socio-emotional skills, well-being, and social outcomes) across three dimensions: quality, access and equity, and efficiency.

The analytical framework encompasses policies on digital education in elementary and secondary schools, vocational education and training (VET), and higher education provided by educational institutions. Digital education refers to any teaching and learning modalities augmented by digital technology, including online, hybrid, and blended formats. Digital technologies encompass networks (e.g., Internet), hardware, software, and technology-related services. The framework model emphasizes the educational applications of these digital technologies, excluding their alternative purposes such as institutional planning, corporate operations, administration of physical and human resources, or research.

The framework was constructed based on various evidence from research, worldwide digital education regulations, and general resource allocation strategies for educational institutions. It considers established best practices for digital education policy, as evidenced by the digital transformation of education systems and current digital competence frameworks.

Fig. 3.1 – Analytical framework for a digital education policy ecosystem: Overview [Reproduced from OCDE (2023)]

3.1 Analytical dimensions and policy levers

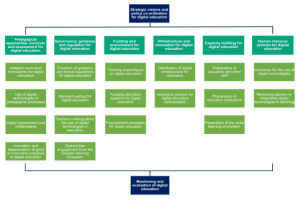

Effective digital education necessitates the utilization of various policy mechanisms that function at multiple intervention levels and influence diverse stakeholders within the education system, including students, teachers, institutional leaders, and public authorities. Some policy levers pertain to education policy, while others are associated with different policy areas and necessitate coordination with relevant authorities in those sectors. Policies for digital education should be evaluated in relation to the specific governance environments of education in which they operate, adapting to the opportunities and needs presented by emerging technologies. The effectiveness of digital education policies should be evaluated based on their impact on various educational outcomes. This necessitates an understanding of the complex interactions between digital education policies and other policies that enhance student skills, well-being, and overall social and labor market results.

Fig. 3.2 – Analytical framework for a digital education policy ecosystem: Analytical dimensions and policy levers [Reproduced from OCDE (2023)]

A robust digital education policy ecosystem must be centered on a strategic vision for digital education, outlining specific policy measures and aligning them with the goals of the education system. The strategic vision must connect with policy coordination mechanisms to ensure that education-specific policies align with the broader policy ecosystem to effectively implement digital education. This encompasses coordination within the education sector (e.g., aligning with other educational priorities or strategies), across various policy dimensions and levels of the system (e.g., engaging with relevant stakeholders in digital education), as well as beyond the education sector (e.g., collaborating with other policy areas). A strategic vision for digital education should incorporate mechanisms for foresight and scenario planning to proactively respond to future societal, technological, and economic changes.

Education policymakers can utilize various policy instruments to realize their strategic objectives for digital education. The analytical framework categorizes these policy levers into eight dimensions (as indicated by the dark green boxes in Figure 3.2), with each dimension examined in detail in the corresponding chapters of this report. In addition to the strategic vision for digital education, the analytical dimensions encompass:

- Adapting pedagogical approaches, curricula, and assessments, including policies that facilitate the selection of appropriate digital education technologies, the dissemination of effective pedagogical practices utilizing digital tools, the modification of curricula and assessment frameworks, and strategies to address barriers that hinder the adoption and effective utilization of digital technologies in teaching and learning.

- Governance, guidance, and regulation for digital education involve the provision of standards and legal frameworks that facilitate the effective and secure utilization of digital education technologies. This includes defining responsibilities for decision-making in digital education and creating participatory mechanisms for stakeholder engagement and coordination with the private sector.

- Funding and procurement for digital education involve enhancing transparency and efficiency in expenditure, developing funding frameworks that align with digital education policy objectives, and improving institutional procurement strategies and budgeting practices.

- Infrastructure and innovation in digital education necessitate policies that guarantee equitable access to and sufficiency of digital education technologies for students and educational institutions. This encompasses distribution mechanisms for digital education technologies that facilitate the attainment of specific policy objectives, including strategies aimed at bridging digital divides among educational institutions. It necessitates multi-dimensional and coordinated policy efforts to foster innovation in digital education technologies, such as tax incentives, grants for business research and development, and the reduction of regulatory burdens for start-ups.

- Enhancing digital education capacity among educators, educational institutions, and stakeholders within the broader learning ecosystem, including specialized personnel, parents, and local administrators. The dimension encompasses various policy levers, including the initial education and ongoing professional development of educators, as well as the facilitation of peer learning and communities of practice. The text examines the role of governments in offering educational institutions guidance on integrating digital education technologies, enhancing leadership, and bolstering their capacity for institutional improvement strategies related to digitalization.

- Human resource policies for digital education should focus on adapting career structures, progression criteria, and working time arrangements to empower and incentivize educators in the effective use of digital technologies within their teaching practices.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, fostering inclusive digital education within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) requires a multifaceted approach, as this document outlines. Key to success is the development and implementation of robust policies that promote equitable access, support diverse learning needs, and integrate universal design principles. Through categorizing policy levers—such as regulation, funding, organization, and information—HEIs can better address access, equity, and quality challenges. Moreover, aligning these policies with comprehensive digital education frameworks, like those proposed by the OECD, can help HEIs adapt to the evolving digital landscape. Collaborative efforts among educators, administrators, and policymakers, combined with strategic planning and resource allocation, are essential for creating a digital ecosystem that supports all learners. These efforts pave the way for a more accessible, inclusive, and resilient digital education environment, ultimately preparing HEIs for future advancements and challenges in education.

5. References

Kottmann, Andrea, et al. “Social inclusion policies in higher education: Evidence from the EU.” Overview of major widening participation policies applied in the EU. Publications Office of the European Union (2019). https://doi.org/10.2760/944713

de Boer, Harry F., et al. “Performance-based funding and performance agreements in fourteen higher education systems.” Center for Higher Education Policy Studies, Universiteit Twente (2015).

Veerman, C. P., Berdahl, R. M., Bormans, M. J. G., Geven, K. M., Hazelkorn, E., Rinnooy Kan, A. H. G., … & Vossensteyn, J. J. (2010). “Threefold Differentiation. For the sake of quality and diversity in higher education”.

A global review of selected, digital inclusion policies, Key findings and policy requirements for greater digital

equality of children. UNICEF INNOCENTI – Global Office of Research and Foresight.

OECD (2023), “Building a digital education policy ecosystem for quality, equity and efficiency“, in Shaping Digital Education: Enabling Factors for Quality, Equity and Efficiency, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1de35897-en.

1. Leadership/ School’s perspective

Inclusive Digital Strategy and Policy for Empowering Inclusive Digital Education

Communication of the policies for enabling inclusive digital education

10 min

(i) Understand the role of inclusive digital education policies

(ii) Identify and categorize policy levers

(iii) Examine best practices and frameworks

(iv) Evaluate the impact of digital policy ecosystems

Higher Education Policies, Digital Education Ecosystem, Equity in Education, Inclusive Digital Education

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them (2022- 1 -SI01 -KA220-HED-000088368).